For years, I dealt with daily diarrhea, bloating, cramping, and pain that were disruptive and impossible to ignore. Practitioners labeled it IBS (irritable bowel syndrome), more a symptom bucket than a true diagnosis. I underwent an upper GI series with dye. One internal medicine doctor pushed for an EGD with biopsies “to see what’s going on,” but when I asked if results would change treatment, he said no. So, I declined.

He never mentioned he was likely checking for celiac disease. If he had, I’d have consented. Later, I realized I likely had undiagnosed celiac or severe gluten sensitivity, plus SIBO, high inflammation, and dysbiosis (an unhealthy microbial balance).

Childhood antibiotics for ear infections and daily minocycline in college for perioral dermatitis probably played roles. Nobody connected any of those dots or explained the gut‑health implications when they prescribed minocycline.

The common thread? A compromised gut barrier—leaky gut, or what the medical literature calls increased intestinal permeability.

This is the first post in a series on leaky gut: what it is, what causes it, how it connects to inflammation, the microbiome, weight gain, food sensitivities, and autoimmune conditions, and what you can actually do about it. I also go deeper into leaky gut in my book God’s Prescription.

But it starts here, with the foundation, because you can’t address something you don’t understand.

What Your Gut Lining Actually Does

Your intestinal lining is one of the most remarkable structures in the human body. Laid flat, it would cover hundreds of square feet—about the size of a small apartment—and it performs a job that requires extraordinary precision: letting the right things through while keeping everything else out.

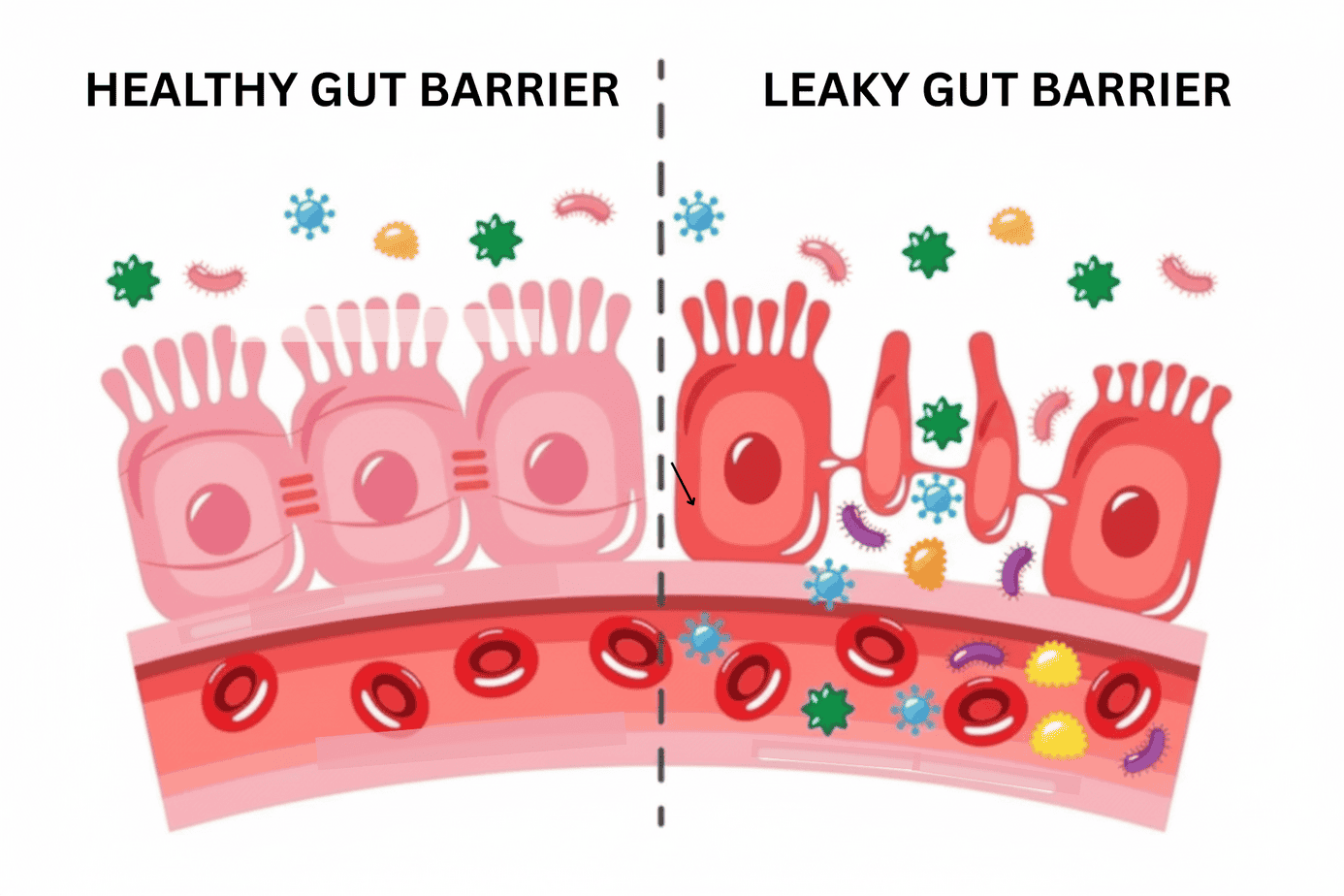

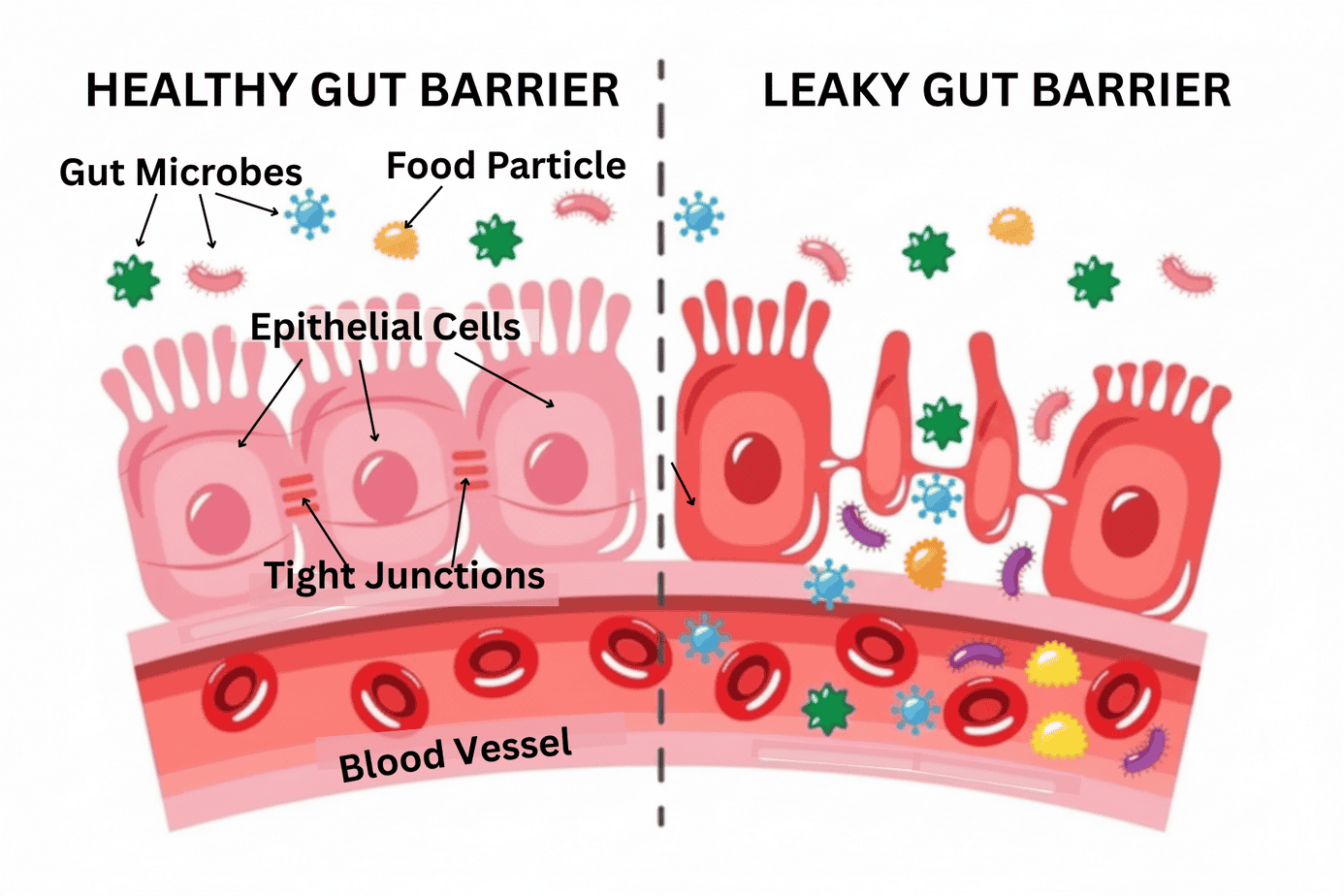

Think of it as a fine‑mesh screen. Water and nutrients pass through easily. Larger particles like undigested food, bacteria, and toxins should stay on the other side. A system of proteins called tight junctions makes this work. They act like seals between the cells that line your intestinal wall. When tight junctions are intact and functioning, the barrier holds. When they loosen or break down, the “mesh” develops gaps.

A key regulator of tight junctions is a protein called zonulin. Discovered by gastroenterologist and researcher Dr. Alessio Fasano, zonulin helps control how open or closed these junctions are. Fasano’s research, published in top‑tier journals, emerged directly from his work on celiac disease. His studies showed that gliadin (the specific protein fraction in gluten) can trigger zonulin release in the human gut.

Although the response is stronger and often more prolonged in people with celiac disease and in some with non‑celiac gluten sensitivity, it’s measurable in healthy people as well. When zonulin increases, tight junctions loosen, and the barrier becomes more permeable.

God designed an elegant system. Your gut lining isn’t passive tissue; it actively senses, responds, and regulates. The problem isn’t the design. The problem is that modern life puts that system under a level of assault it was never built to withstand indefinitely.

So, What Is Leaky Gut?

If you’re wondering what leaky gut is, leaky gut (also called intestinal permeability or increased intestinal permeability) occurs when tight junctions stay open too long or too often. When the barrier is compromised, partially digested food particles, bacterial fragments (including a particularly problematic one called LPS, or lipopolysaccharide), and other substances pass through the gut wall into the tissues and bloodstream.

Your immune system detects those particles as foreign or out of place and mounts a response. That response is inflammation—not the acute, purposeful inflammation of healing a cut, but chronic, low‑grade, systemic inflammation that doesn’t fully resolve because the trigger never really stops.

That chronic inflammation is where many downstream conditions begin. But we’ll come back to that.

First, a note on the name. “Leaky gut” is the lay term that naturopaths and other holistic practitioners used for years. “Intestinal permeability” is what conventional medicine calls it, and what you’ll see in the peer‑reviewed literature now that it has been acknowledged. At the time of this writing, a PubMed search (the National Library of Medicine’s research database) returns over 31,000 papers on intestinal permeability.

The science behind leaky gut—what I’ll call the leaky gut science—is not fringe, and the research is not new. What is relatively new—and still evolving—is the mainstream willingness to take it seriously.

Why So Many Practitioners Still Dismiss It

People have called leaky gut a myth, a fad, and a marketing term. It has been laughed at in clinical settings. A few years ago, a client’s gastroenterologist attended a continuing medical education conference and came back confidently reporting that there is no test for leaky gut.

Comments like these reflect a broader issue: most practitioners trained within models that did not include intestinal permeability as a diagnosable condition. There is no ICD code and no pharmaceutical treatment, so it receives little attention in medical education or industry-sponsored training. Further, conventional visits are short and protocol-driven, which leaves little room for root-cause investigation. That is not a conspiracy. It is an incentive structure.

The irony is profound: celiac disease, one of the best-studied gut barrier disorders in medicine, shares the core mechanism (gluten triggering tight junction dysfunction and increased permeability). It’s undisputed in that context, but the principle isn’t applied more broadly.

Functional medicine practitioners test for intestinal permeability. However, they often rely on history, symptoms, and response to interventions since no single lab marker is universally standardized. Additionally, most tests aren’t covered by insurance. Available tests include the lactulose–mannitol challenge, serum or stool zonulin, and occludin/zonulin antibodies.

To be fair, there are conventional and integrative physicians who understand and address gut barrier health; they are just not yet the norm.

What Leaky Gut Is NOT

Common misconceptions about leaky gut:

-

- It is not just a “sensitive stomach.” Digestive sensitivity is one possible symptom, but leaky gut is fundamentally an immune‑activation problem: a barrier failure that triggers systemic inflammation. The gut symptoms may be only the beginning.

- It is not only about digestive symptoms. Bloating, cramping, diarrhea, constipation, and pain are all common, and my own story started there. But the downstream effects extend far beyond the gut.

- You do not have to “feel it” in your gut to have it. Many people with significant intestinal permeability have no obvious GI symptoms. Their symptoms show up as skin conditions, joint pain, brain fog, fatigue, food reactions, or autoimmune flares, so they never think to look at their gut.

- It is not one single disease or defect. It is a pattern of barrier dysfunction with multiple causes and multiple contributing factors.

- It is not rare. Given how common the causal factors are in modern life, intestinal permeability is increasingly understood as widespread.

What Causes Leaky Gut: The Dirty Dozen

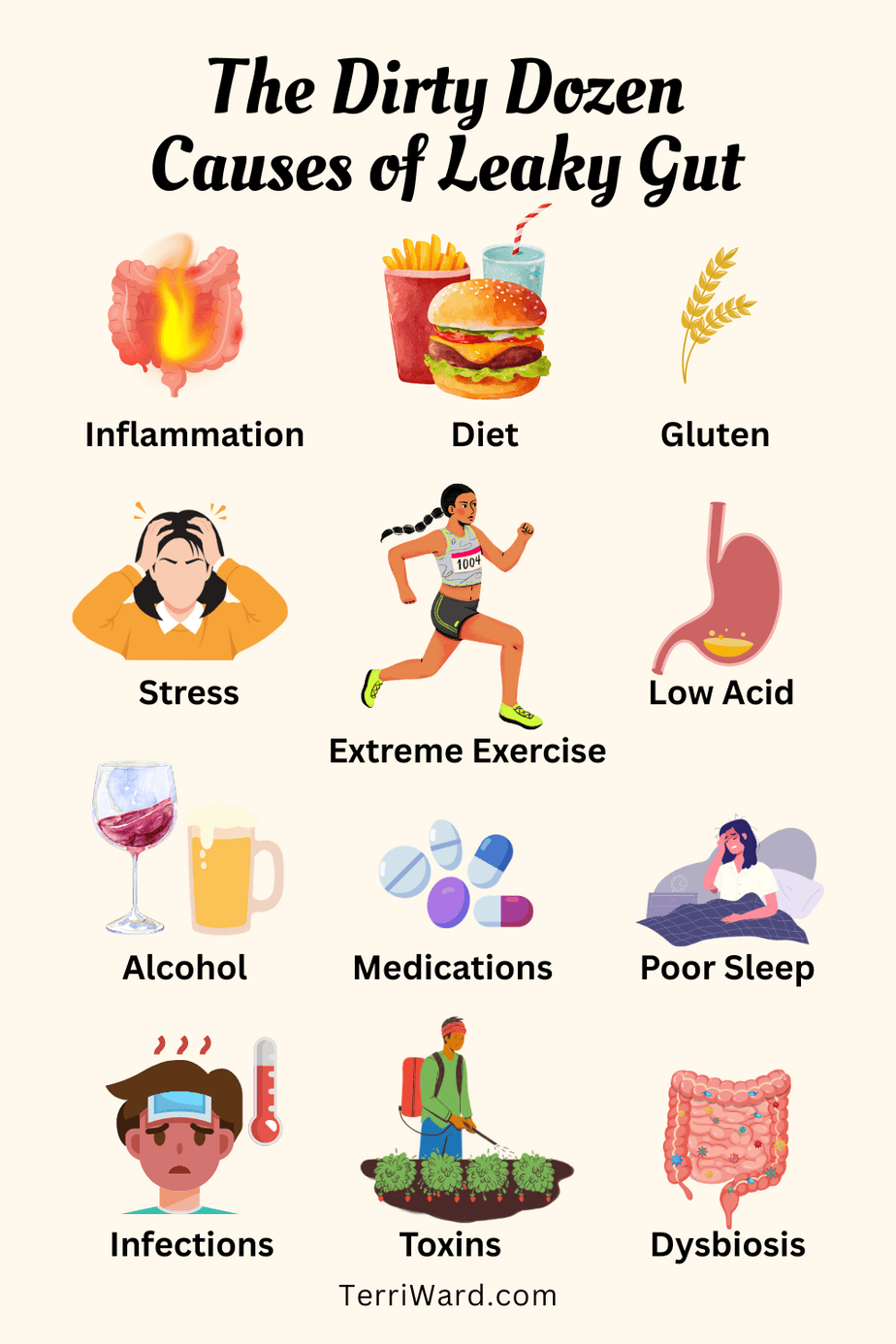

- Chronic inflammation. Creates a vicious cycle: inflammation damages the gut barrier, which allows more inflammatory triggers into the bloodstream, which drives more inflammation.

- Poor diet. Ultra-processed foods, industrial seed oils, excess sugar, and refined carbohydrates can damage the gut lining, displace the dietary fiber that protective bacteria need, and feed microbes that produce compounds increasing permeability. Even some whole foods contain antinutrients (lectins, phytates, oxalates) that may irritate the gut lining in susceptible individuals or when consumed in excess.

- Gluten. Triggers zonulin release, loosening tight junctions. Modern hybridized wheat amplifies this, producing gliadin peptides more likely to provoke immune responses and loosen tight junctions, even if the gluten quantity hasn’t changed.

- Chronic stress. Stress hormones change how food moves through the intestines, blood flow to the intestines, and how blood and immune cells behave along the gut lining. Over time, these changes weaken the barrier, loosen tight junctions, and alter the microbiome, making the gut more permeable. The gut–brain axis runs in both directions, and stress signals reach the gut quickly.

- Extreme exercise. Moderate exercise is beneficial, but prolonged high‑intensity exercise shunts blood away from the gut to working muscles, starving intestinal cells of oxygen and injuring the barrier. This helps explain why endurance athletes often have GI issues during events.

- Low stomach acid. Without adequate acid, proteins are not fully broken down before reaching the small intestine, so they remain as larger peptides that can trigger immune reactions and barrier damage. Stomach acid also helps neutralize pathogens that hitch a ride on our food, preventing bacterial overgrowth and infection downstream.

- Alcohol consumption. Alcohol directly damages intestinal epithelial cells and disrupts the mucosal barrier, especially with regular or heavy use.

- Medications like NSAIDs, antibiotics, and PPIs. NSAIDs (aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen) damage the gut lining with regular use; antibiotics disrupt microbiome diversity and eliminate protective bacterial species; proton pump inhibitors (PPIs like omeprazole) suppress stomach acid and alter gut pH, promoting dysbiosis and increasing infection risk.

- Poor sleep. The gut does significant repair work during sleep. Chronic sleep deprivation impairs that repair, alters circadian regulation of the gut, and shifts microbiome composition in a pro‑inflammatory direction.

- Infections. Certain bacterial, viral, and parasitic pathogens directly damage the intestinal barrier, and post-infectious gut dysfunction is real and underrecognized.

- Environmental toxins. Pesticides, plastics, heavy metals, and other pollutants can disrupt tight‑junction proteins, injure beneficial gut bacteria, and activate inflammatory pathways that compromise the barrier. In my own case, I struggled with symptoms of leaky gut and got nowhere doing “all the right things” until testing revealed toxic levels of uranium in our water supply; once I removed that exposure and supported detoxification, my gut could finally heal.

- Unbalanced gut bacteria (dysbiosis). An imbalance between beneficial and harmful microbes removes key support for the gut lining. Beneficial bacteria produce short-chain fatty acids like butyrate that are essential for tight junction integrity and gut cell health. Dysbiosis and leaky gut form a self-reinforcing cycle, each making the other worse.

Dysbiosis is a larger part of this story. In upcoming posts, I’ll show you how dysbiosis develops, how the microbiome and leaky gut feed each other, and what you can do about both. If you want to follow along, make sure you’re subscribed so you don’t miss the rest of the series.

For weekly Scripture, wellness tips, and anti-inflammatory recipes delivered to your inbox,

Subscribe to the newsletter below.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Why This Matters Far Beyond Your Gut

Understanding what leaky gut is matters because its effects extend far beyond digestion. Once the barrier breaks down and foreign particles enter the bloodstream, the immune response that follows affects the entire body. Substantial, growing research connects leaky gut to systemic disease.

Peer‑reviewed studies have linked increased intestinal permeability to issues like:

-

- Autoimmune conditions (including rheumatoid arthritis, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, lupus, and multiple sclerosis)

- Food sensitivities

- Eczema and psoriasis

- Neurological conditions including depression and anxiety

- Obesity and metabolic dysfunction

- Type 2 diabetes

- Cardiovascular disease

- Non‑alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

Although there are other contributing factors that cause these conditions, healing can remain elusive if leaky gut is overlooked. The relationship is complex, bidirectional in some instances, and still being studied. But the pattern is consistent enough across the literature to say clearly: a damaged gut barrier is not a local problem. It is a systemic one.

If you have struggled with weight that does not respond to diet and exercise, energy that does not respond to sleep, or symptoms that nobody has been able to explain, the gut barrier is a piece of the picture worth examining.

The connection between leaky gut, inflammation, and metabolic dysfunction is covered in depth later in this series.

Where This Leaves Us

For a long time, I had symptoms, a label, and no real answers. Once I understood what was actually happening—a gut barrier that had been compromised by years of antibiotics, a diet full of gluten and processed food, and a stress load that was not being managed—I finally had something I could work with.

Understanding the mechanism is the first step. You cannot support something you do not know exists. That is what this post is for.

In the next post in this series, we will go deeper into the inflammation piece: what it looks like systemically, why it does not resolve on its own once the barrier is compromised, and what that chronic immune activation is actually doing to your body over time.

Ready to Get to the Root?

If you recognize yourself in any of this—the dismissed symptoms, the labels without answers, the sense that something deeper is going on that nobody has been able to name—this is exactly the work I do. I help people with autoimmune conditions, food sensitivities, and other gut‑related issues understand what is driving their health challenges and build systems to address them.

If you are ready to stop managing symptoms and start addressing causes, I would love to talk. You can book a free 15‑minute chat with me here.